We can argue that corrupt practices should be stopped, but really, at times, there is simply no alternative.

I hope that the title does not evoke feelings of solidarity. We have learned to identify with the multitude of diatribes against the endemic prevalence of this social evil – ‘corruption’. The internet and print media have become deluged by these publications, which seek to skim the surface of this issue. It is like eliminating the iceberg as one of the causes behind the sinking of the RMS Titanic because the portion visible above the sea did not hit the ship.

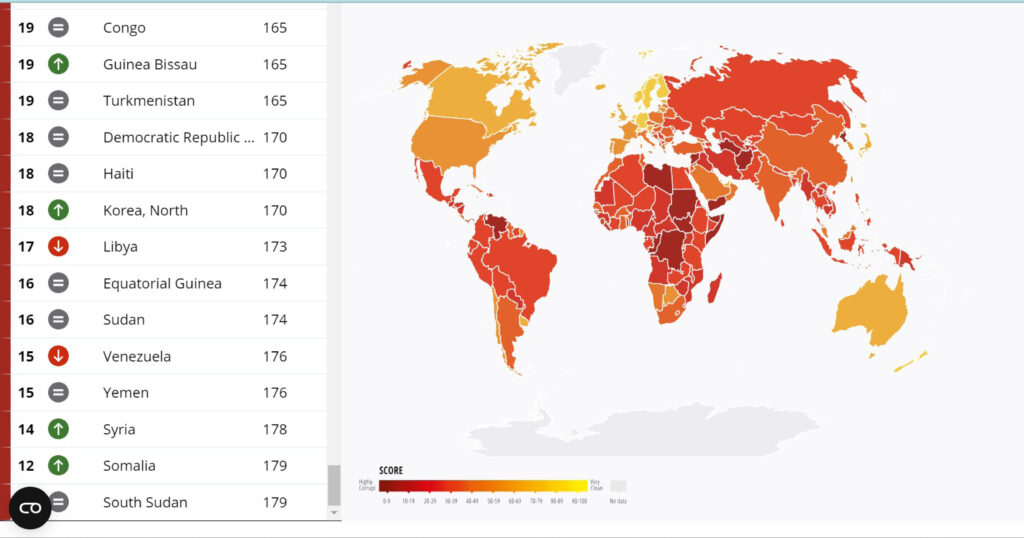

Fig.1: The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) ranks of countries around the world. Towards Red = Highly corrupt; Towards Yellow = Very clean; Grey = No data.

Without considering anthropological and sociological factors, an analysis of this corruption leaves much to be desired, especially when it comes to the ‘Why?’.

Let’s look at the Corruption Perception Index data [Fig.1] published annually by Transparency International since 1995. The bottom-most countries for 2020, in the descending order of their performance were – Venezuela, Yemen, Syria, Somalia, and South Sudan. For 2009, they were Iraq, Sudan, Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Somalia.

If we rewind a decade from 2009, we arrive at different countries – Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Cameroon. What changed from 1999 to 2009 for these countries, and what tragedy befell the countries forming the bottom 5 in 2009? If we carefully peruse the scores of the bottom-ranking countries in particular, some noteworthy patterns stick out.

With a few exceptions, these countries are not among the poorest or countries with the lowest economic growth rates but end up trailing all the rest of the countries when it comes to corruption. The most apparent and regrettable feature common to most countries is that they have been afflicted by internal strife.

Consider Nigeria in 1999, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia in 2009 and Yemen, Syria, and South Sudan in 2020. There had been an authoritarian military junta in Nigeria since 1983. Despite the economic growth achieved due to oil exports, little wealth generation reached the agrarian tribal sects dominating the demographics. Cameroon faced a similar situation with widespread allegations of corruption facing the incumbent government and insistence to look inwards for resources due to unacceptable terms for credit by the IMF and World Bank.

Coming to 2009 and 2020, we are all too aware of the developments in the Middle East – the war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan and later the onset of domestic strife and revolt that started with the Arab Spring movement. It spread to several countries, including Syria, where it has escalated to full-scale civil war. The recently created nation of South Sudan is also ravaged by ongoing civil unrest between sectarian forces and the military, as is Yemen. These countries have a fragile ecosystem for creating and distributing wealth and economic resources due to being war-ravaged for several years (more than a decade for Syria).

A significant portion of the population depends on various economic activities for survival – especially in the services and agricultural sectors. When there is an ongoing crisis of this scale, there is a severe disruption in these sectors for several months or years. The manufacturing sector comparatively faces less disruption and more distortion in terms of the products as they are retooled to support the state’s efforts to resolve the crisis.

People who were dependent on these economic activities, now rely on the government for support to get by during the crisis to resume and recoup their losses after the crisis has been dealt with. Let’s re-look at the countries again – Yemen, South Sudan (2020), Iraq (2009). Yemen and South Sudan do not have the resources to support their population. The penetration of government institutions like law enforcement is too superficial to ensure equitable aid distribution during a crisis.

The logical and even practical way forward to ensure the distribution of resources in this scenario is to have a first-come-first-serve policy, at least in countries where there is some semblance of law enforcement down to the local levels where the government interacts directly with the people. But the lack of institutions at such levels will only ensure that there are riots when people realize that the resources are probably insufficient for most seeking aid.

It is where people with comparatively more wealth come forward and seek to allocate resources for themselves by dealing directly with people in the government. We can argue that this is corrupt and should be stopped, but really at times, there is simply no alternative. These people then distribute the remaining resources based on personal contact with the rest of the people or by selling them and acting as middlemen. For example, you can imagine that people from the same village may get resources allocated if someone from their town is among those few who have obtained them using these “corrupt” practices.

As the years go by with the never-ending crisis, the society gets by with this informal arrangement and starts to make peace with it, understanding its necessity in such times.

Yemen’s humanitarian crisis and economic struggle

A prime example is the erstwhile Soviet Union, where all the necessities like housing, food, clothing etc., were allocated by the government and were never adequate compared to the demand of living drastically (the average wait time for public housing in the USSR was 30 years). Even in India, it was only marginally better for the most part since independence, and some vestiges remain from that time. Many of you will be familiar with buying a new Fiat or Bajaj Scooter in the 70s and 80s.

According to the USSR propaganda, Soviets lived in a land of plenty, where everything was provided for by the state. In reality, getting a car, an apartment or decent clothes was close to a dream for most families.

A communal kitchen in a shared apartment in USSR

A slightly different perspective throws light on the survivalist instinct of cohorts who have been through a prolonged crisis period – extreme poverty, civil war, famine etc. There is a tremendous psychological impact such events leave on the mental well being of the survivors, and this affects how they begin to interpret their surroundings and decision-making even years after their lives got better after overcoming the unfortunate phase.

Even the slightest change for the worse in their newfound peaceful existence can trigger these survival instincts, where the priority is to get by another day. Participating in corruption takes a backseat when it comes to viewing it through the lens of morality.

Considering all of this, it becomes somewhat easier to understand why people in the West are psychologically affected by the thought of condoning bribery. At the same time, we have an almost nonchalant reaction in the East (more societies in Asia and Africa are tolerant of corruption than in the West).

The most important fact to consider is that in the West, the majority of the people are not participants. Such a situation where the distribution of resources is critical because of an ongoing crisis, rarely arises in contemporary western society. Even when it does – for example, in WWII, the state institutions are adequate to ensure no social disruption to affect an equitable distribution of resources.

The Herd Mentality is also a likely factor here. In the West, few people are participating in corruption which makes it easier to put down the blame on the criminality of such an activity. However, in countries described above that have an ongoing crisis threatening national security and when such events are a part of the population’s daily reality of existence, it is easy for the Herd Mentality to overcome inbuilt beliefs or principles which may have caused one to see participating in such dealings as a crime.

Featured Image Source:

References:

- Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI)

- E-International Relations, The Crime of Hunger: Yemen’s Humanitarian Crisis

- The New York Times, In Soviet, Ingenuity Is Needed to Find an Apartment

- Asch, Solomon E. “Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority.” Psychological monographs: General and applied 70.9 (1956): 1.

Comments