Should We All Have the Right to be Forgotten?

A concept of the Internet Age.

Imagine an embarrassing photo, a controversial tweet or a random thought on Reddit – all of which lose their relevance to your mind within minutes and to the topic within hours or days. But, the internet will remember forever until the electricity powering the servers is cut off. So then, what good is this artificial increase in the public’s memory, whereby you can be held accountable for an opinion you had ten years ago and subsequently be ‘cancelled’ for it?

The modern communications megalith sees all, remembers all and spares none! Investigations are swift at the click of a button, and justice is dispensed through the easily manipulated will of the masses.

Save for a situation wherein a crime has been committed, pushing a person to be perennially worried about what they used to think during a different time of their life is akin to keeping them and their freedom hostage. So it is not unexpected that there have surfaced demands to be ‘forgotten’ by the internet – to fade away from the public consciousness and become ‘lost to history’.

So what is this new right, enshrined in tenets of dignity and privacy, the ‘Right to be Forgotten’?

In principle, it allows a person to seek deletion of private information from the Internet. The concept has been recognised in some jurisdictions abroad, particularly the European Union (EU).

While the right is not recognised by law in India, courts have held it an intrinsic part of the right to privacy in recent months.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the EU provides for the right to the erasure of specific categories of personal data — that which is considered no longer necessary, that for which consent has been withdrawn or processing of which has been objected to, personal data unlawfully processed, and data where there is a legal obligation for erasure.

Leaving aside the legal jargon, suffice it to say, unless there is a criminal association of the data or it is being used for the public good – like health statistics – every individual must have the right to choose what data is retained about them on the Internet. And many companies have stepped forward to meet this newly felt need.

Technology-Based Surveillance

While the social media giants under Meta Inc. allow you to view and delete your data and most others allow you to delete your account and assure you of permanent deletion of your information, more often than not, your “anonymised” data is being used in a “quality improvement” programme. Third-party privacy apps, such as Mine, have emerged with an assurance to find all your data everywhere and purge it from the web via data erasure requests sent to individual apps and services.

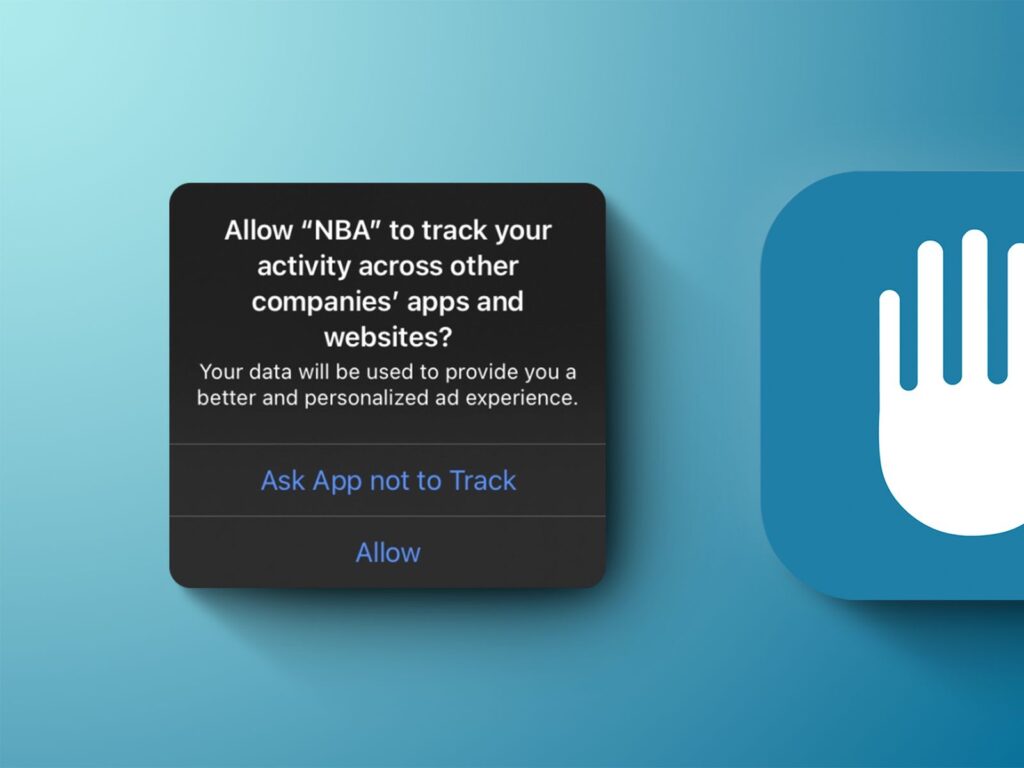

With the ‘privacy’ angle being focussed on quite frequently in the past few years and people complaining of advertisements awkwardly similar to the conversation they just had minutes ago with their friend, device manufacturers have built-in support to disable the microphone and camera access for the overly paranoid.

But when push comes to shove, most of us are not concerned with the overarching surveillance that has become a regular part of our lives. As we install a new app, we hurry to grant permissions to it and have it working for our needs ASAP – but is the app working for you, or is it the other way around?

Privacy settings

A common argument against this line of thought is that the public has the right to know. The real question is something else:

Does this right to information supersede the right to privacy that an individual is guaranteed as a citizen?

Of course, the fact that any controversial information can be deleted ensures that people would save a copy for future reference.

It remains to be seen whether this possession of someone else’s ‘forgotten’ information would be violating their privacy. Additionally, subject to the Streisand Effect, the deletion of information on a particular topic would just draw more attention to it and might be counterproductive with regards to the original intention.

Much is yet to be done to resolve this debate of personal privacy vs public curiosity. The consequences of any decision in this matter would be far and wide-reaching. With implications not only on how an individual’s data is stored but also on what, where and how people choose to express themselves, knowing that every word they say, sign or type has the possibility of being misinterpreted or politically incorrect, a few years down the line.

Featured Image Source: