The discovery of drugs has changed the course of Humankind’s history. Countless lives have been saved from the clutches of mortality and morbidity. The average life expectancy has risen from 29 years in the 19th century, to 73 years in the 21st century. Experimentation, innovation, and mass production of drugs have acted as well-oiled cogs in the business of saving lives. But there’s a caveat. As the Swiss Physician Paracelsus puts it, all drugs are poison. At the promise of relief, many humans have endured suffering. The science of Pharmacovigilance uses the term Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) to label any harmful, and unwanted effect produced by a drug. But this piece is not going to be a winding technical exposition about Drugs, Mechanism of action, Causality assessment, and such. This piece hopes to be a sympathetic account of some of these incidences when drugs have harmed humans in large numbers and have influenced our relationship with drugs.

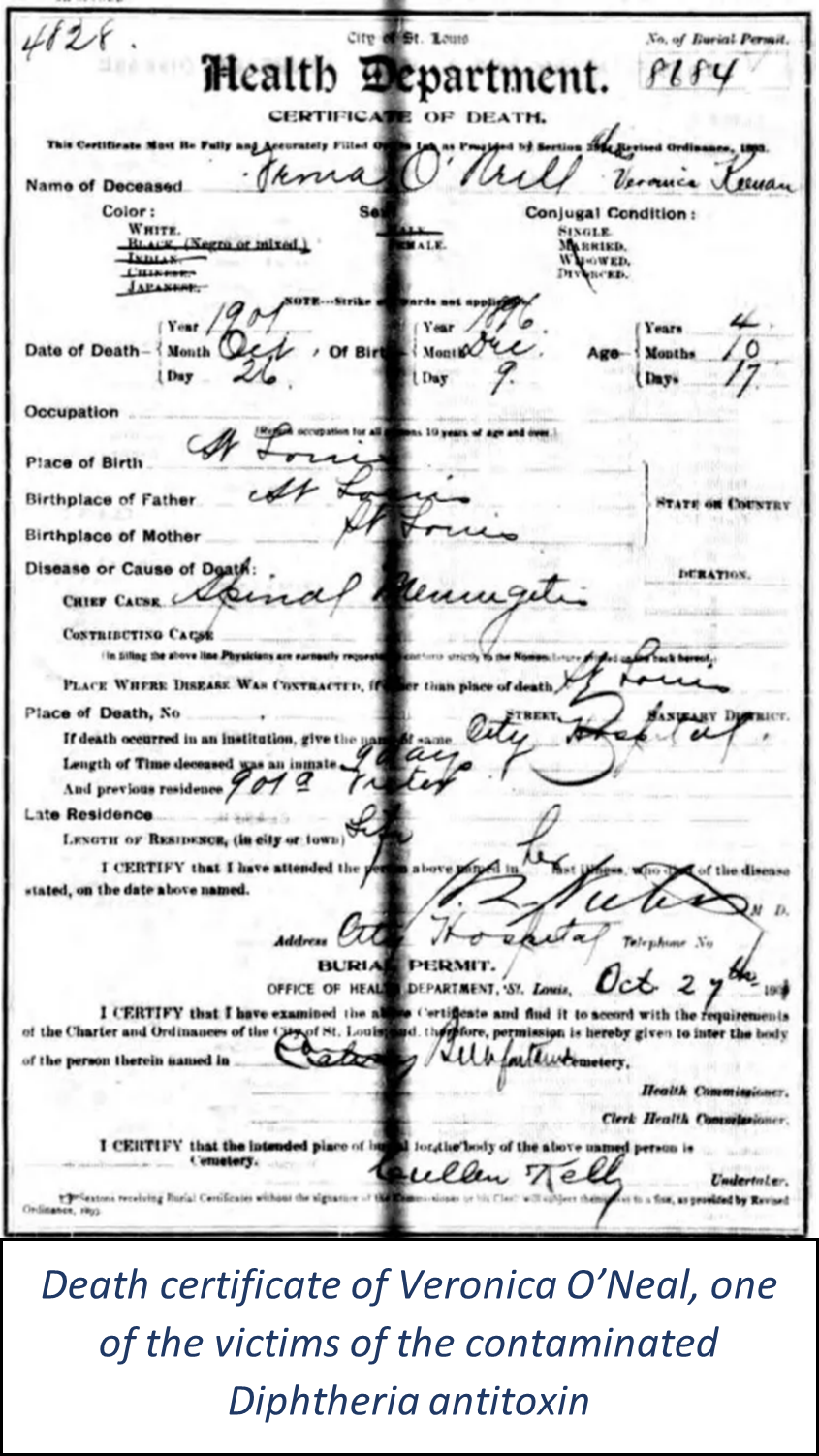

On 19th October 1901, in St. Louis, Missouri, a physician, Dr R.C. Harris, attended young Bessie Baker. Bessie was showing signs of advanced Diphtheria. Dr Harris gave her a routine shot of Diphtheria antitoxin, and as a precaution, her 2 younger siblings as well. This routine exercise would soon turn into a nightmare for Dr. Harris. 4 days later, Dr Harris followed up on Bessie and found her suffering from lockjaw. It was too late to give her any medical aid. She died the next day, and her siblings followed within a week. Reports of similar deaths were notified to the health department of St. Louis. A total of 13 children had died by November 7th.

Diphtheria was a menace in the 19th century. There were more than 100,000 cases yearly in the US alone, and about 15,000 deaths. The first chemical with antibiotic properties was yet to be discovered. In 1890, two scientists, Shibasaburō Kitasato

and Emil von Behring used diphtheria toxin to immunize animals and derived the “antitoxin” from their serum which could cure the disease. This groundbreaking discovery would weaponize doctors against Diphtheria. von Behring won the first-ever Nobel Prize for Medicine for this accomplishment in 1901. By the early 20th century, the use of the Diphtheria antitoxin for treatment and prevention had become commonplace.

As an effort to thwart Diphtheria, the Health Commission of St. Louis, Missouri, started an ambitious project of producing their supply of the antitoxin. Amand Ravold, a former pupil of Pasteur, was appointed to lead this project. But tragedy struck a few years later.

After the deaths of the 13 children in 1901, the health department recalled the antitoxin and started an investigation. Upon the initial investigation, it was found that Dr Ravold bled an old workhorse named

Jim, to produce the antitoxin. But Jim contracted Tetanus and died two days later. So, Dr Ravold ordered the destruction of the antitoxin. But when his janitor, Henry Taylor was rigorously interrogated, he confessed to releasing some serum which was procured from Jim. This tetanus-contaminated antitoxin resulted in 13 deaths. The health department of St. Louis dismissed both Dr Ravold & Taylor. Dr. Ravold, however, defended Taylor, saying that he was merely a good servant, and didn’t possess the judgment or the capabilities to ensure the suitable disposal of the deadly serum.

This incident is described as the first modern medical disaster. Modern because it involved the usage of a therapeutic agent based on principles of modern medicine.

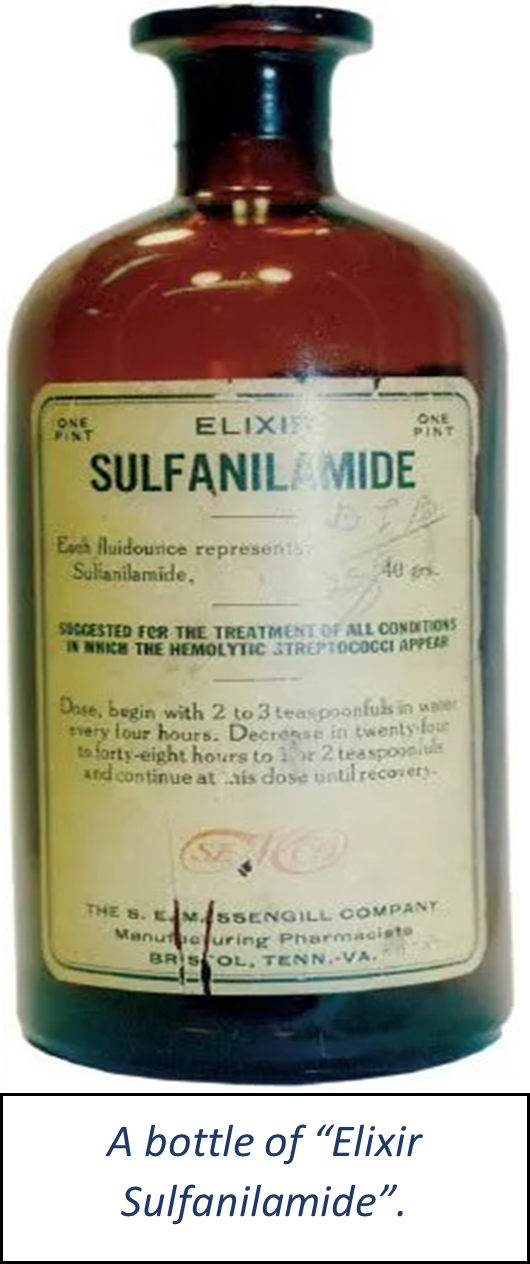

1937 Salesmen of S.E. Massengill & Co.

reported that there is a demand for the drug Sulfanilamide in liquid form. Sulfanilamide was a wonder drug that was used to cure Strep throat. But much like today, it was difficult to convince Children to take a tablet or capsule.

The company decided to give the responsibility of formulating a liquid form of the drug to their chief chemist, Harold Cole Watkins. After a week of experimentation, Watkins finally settled on dissolving the drug in a chemical called Diethylene Glycol. He used Raspberry extract, saccharine & caramel to make it more palatable for the kids. The company also approved the flavor and the appearance of the new formulation. They named it “Elixir Sulfanilamide”. Massengill was already salivating at the prospects of the profits this would earn them. They began distributing samples to doctors.

About a month later, in October 1937, the American Medical Association (AMA) began receiving reports of deaths of Children. All of them had been affected by Step throat and had died exhibiting similar symptoms: they were cold, had slow & shallow breathing, and were not producing urine. They had one more thing in common. They were all prescribed Massengill’s new “Elixir Sulfanilamide”. When the AMA reached out to Massengill to learn more about their new formulation, they learnt to their great horror about Diethylene glycol being employed as a solvent for Sulfanilamide. Diethylene glycol had recently been found to be a fatal substance even in small doses. The Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) was alerted about this new product, but to no avail. Even though it was poisonous, the FDA were powerless because the existing legislation then didn’t mandate safety testing of new products before marketing. The FDA eventually charged Massengill with mislabelling, as “Elixir” typically refers to a product containing alcohol, and the “Elixir Sulfanilamide” didn’t contain any. They issued a recall of the product. The process of recall exposed another issue, of wrong prescription practices. It was a complex exercise for the FDA to track down and seize all the sold bottles. Salesmen and pharmacies didn’t have a proper record of where the bottles went through them. Since Sulfanilamide was also used to treat Gonorrhoea, it was suspected that a lot of people had used fictitious names and addresses to avoid public embarrassment. The FDA had to employ their detective skills, but it was a slow process and the death toll kept rising.

Dr Archie Calhoun of St. Olive, Mississippi recorded his anguish:

“Nobody but Almighty God and I can know what I have been through in these past few days. To realize that six human beings, all of them my patients, one of them my best friend, are dead because they took medicine that I prescribed for them innocently, and to realize that the medicine that I have used for years in such cases suddenly had become a deadly poison in its newest and most modern form, as recommended by a great and reputable pharmaceutical firm in Tennessee; well, that realization has given me such days and nights of mental and spiritual agony as I did not believe a human being could undergo and survive. I have spent hours on my knees, once I had done all any physician could do for his patients. I have known many hours when death for me would be a welcome relief from this agony.”

By the time the FDA managed to seize all the Elixir Sulfanilamide, 68 were confirmed and about 30 probable deaths had occurred due to it. Samuel Evans Massengill, the owner of the company said:

“My chemists and I deeply regret the fatal results, but there was no error in the manufacture of the product. We have been supplying a legitimate professional demand and not once could have foreseen the unlooked-for results. I do not feel that there was any responsibility on our part.”

He was right in principle, as the existing legislation did not call for testing the safety and efficacy of products. The chemist Watkins, however, could not fight this weight on his conscience. He killed himself.

There was a silver lining to all of this. The Sulfanilamide tragedy hastened the enactment of the 1938 Food, Drugs & Cosmetics Act. This act would require testing the safety and efficacy of new drugs before their approval in the United States. It would give more power to the FDA, to resist approval of new drugs, and go behind manufacturers who would market drugs without proper testing. This would protect America from another tragedy that was silently brewing in other parts of the world.

In 1960, Frances Oldham Kelsey was hired by the FDA in a similar capacity. Her job was to review applications by pharmaceutical companies for approval of new drugs to be marketed in the United States. The first application to fall on her desk was by Richardson-Merrell (now a part of Sanofi) for a drug called Kevadon. Kevadon was the trade name for the drug Thalidomide.

Developed in 1951, by Chemical Industry Basel, or CIBA (now Novartis), Thalidomide was found to be non-toxic in animals, but without any therapeutic benefits. CIBA shelved it until 1957 when it was acquired by Chemie Gruenthal (now Gruenthal). Chemie Gruenthal started distributing free samples of the drug, without any clinical trials or any scientific rationale. They started, as an author described it – playing Russian Roulette, with Thalidomide, prescribed it for a variety of indications – Seizures, Flu, Cough, Cold, Insomnia, and Morning sickness. Among these, Contergan gained popularity as a sleeping pill and “anti–morning sickness” pill. Several other pharmaceutical companies in Europe, South America & Canada also started manufacturing and marketing Thalidomide. Tensival, Distaval, Asmaval, Valgraine, and Thalomid – these were some of the brand names of Thalidomide. The sheer number of brand names is enough to suggest the popularity and availability of the drug.

Kelsey had formerly worked with Dr EMK Geiling on the Sulphanilamide mishapening. After reviewing the application for Kevadon, two things struck Kelsey – firstly the drug did not show hypnotic effects, as promised, in animals, and secondly, there was a lack of teratogenicity testing. Kelsey requested Richardson Merrell for further studies and kept requesting for it upon further unsatisfactory submissions. Frustrated, Joseph, Murray, a representative of Richardson Merrell, tried to pressure Kelsey through phone calls, personal visits, and complaints to her superiors. But Kelsey stood her ground firmly.

In November 1961, Kelsey’s resolve would end in great payback. An epidemic of phocomelia – babies born without limbs, or very short limbs, that was gripping Europe, was attributed to Thalidomide. Widukind Lenz, a German pediatrician found that at least half of the

mothers who had given birth to children with deformities had taken Thalidomide in the first trimester of the pregnancy. German authorities pulled the drug off the market within 10 days of Dr Lenz’s warning, and other countries followed suit. In the US, Richardson Merrell withdrew their application. But as a part of clinical trials being run by Richardson-Merrell and Smith, Kline & French (now GSK), 20,000 Americans had received the drug.

It is estimated that 10,000 children born outside of the United States, were deformed because of Thalidomide. Forty percent of these died soon after birth. It’s probable that many more children died silently in their mothers’ wombs. Dr Kelsey’s stand against the drug restricted this statistic to 17 children in the United States.

Frances Oldham Kelsey received the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service in 1962. Kelsey continued working for the FDA. In 1994, she was part of the FDA’s working group to develop and implement uniform standards of safety for clinical studies using Thalidomide. Thalidomide since has been re-introduced in the market, for lepra reactions, and multiple myeloma.

In 2023 the deaths of Children, after consuming Cough syrup, which was manufactured in India made headlines. Allegedly, 66 children in Gambia and 18 in Uzbekistan died. When their deaths were investigated, it was found that the syrups were contaminated with Ethylene Glycol and Diethylene Glycol. The very same Diethylene Glycol that was present in the “Elixir Sulfanilamide”. The very same Diethylene Glycol which had already killed at least 68 people more than 80 years ago. The company Maiden Pharmaceuticals denied any wrongdoing. The inspectors of India’s federal drug regulator did send them a notice regarding mislabelling.

This case is a chilling Déjà vu of the “Elixir Sulfanilamide” disaster. It is an absolute failure at every level that these deaths occurred in the 21st century. But as a pharmacologist in training, it reminds me of the importance of my training. A Pharmacologist like Dr Kelsey would probably not save individual lives daily, like a clinician. But doing their job with honesty and sincerity can safeguard many more lives. It is in a way the embodiment of Hippocrates’s most famous principle – “Primum, non nocere” – First, do no harm.

References:

- DeHovitz RE. The 1901 St Louis Incident: The First Modern Medical Disaster. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2014 Jun 1 [cited 2021 Oct 16];133(6):964–5. Available from: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/6/964

- Silverman, “Elixir of Death – Podcast #106.” Useless Information, 9 Oct. 2017, uselessinformation.org/elixir-of-death/. Accessed 6 Oct. 2023.

- Bren, “Frances Oldham Kelsey: FDA Medical Reviewer Leaves Her Mark on History.” Web.archive.org, 20 Oct. 2006, web.archive.org/web/20061020043712/www.fda.gov/fdac/features/2001/201_kelsey. html.

- “India Probes Bribery Claim in Toxic Syrup Tests.” The Economic Times, 13 June 2023, economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/pharmaceuticals/india- probes-bribery-claim-in-toxic-syrup-tests/articleshow/100972054.cms. Accessed 6 Oct. 2023.