The idea of healthcare being a fundamental right proposes that everyone should have access to healthcare services as a basic entitlement, regardless of their socio-economic status, background or any other circumstance. The rationale is made because everyone should have access to the appropriate medical care to maintain their health and dignity.

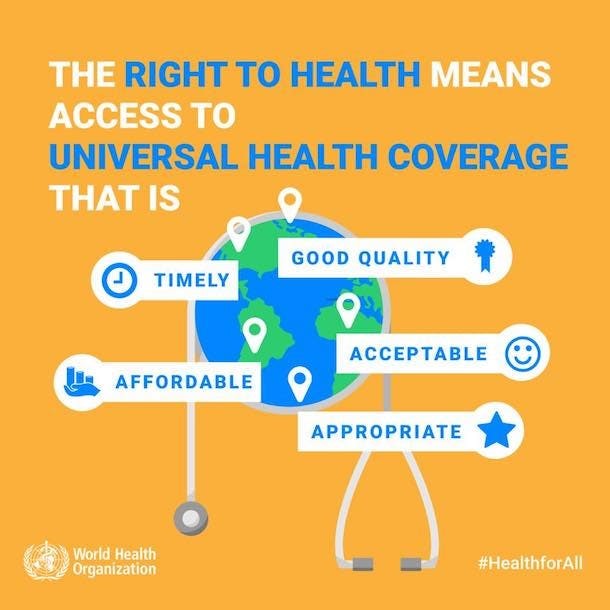

According to the World Health Organisation, everyone has the fundamental right to the “highest practicable form of health”. All citizens are entitled to access their right to health, regardless of their ethnicity, gender, political views, or social & economic circumstances.

The right to health is envisioned by the United Nations (UN) according to the same standards as the World Health Organisation. The right to health is acknowledged in Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). It states that everyone has the right to a quality life that is good for their health, and the health and well-being of their families. These covers having access to food, clothes, shelter, medical treatment, social services, and security of the right to health in the event of unemployment due to illness, widowhood, old-age, or other uncontrollable conditions.

What are the implications?

Moral and humanitarian viewpoint: Access to healthcare is a fundamental human right since it is required to safeguard and maintain human life and well-being. No one should be denied healthcare based only on their inability to pay for it according to humanitarian and moral stances. It is believed that having access to healthcare is a basic component of human dignity and that it is morally necessary to guarantee this for everyone.

Benefits to society and public health: It is suggested that making access to healthcare a fundamental right has advantages for society. Early detection of disease and treatment, stopping the spread of infectious diseases, and better overall public health outcomes can all be attributed to access to healthcare. People are more inclined to seek prompt medical attention when they have access to healthcare, which can stop problems from getting worse and lessen the financial burden of illness in society.

Social justice: Promoting healthcare as a fundamental right is crucial for eradicating health inequalities and advancing social justice. No one’s ability to get healthcare should be based on their financial or social standing, rather, it should be provided to all people equally. The provision of healthcare as a fundamental right is viewed as a means of fostering equity and fairness in society and ensuring that underprivileged groups have access to crucial medical services.

When the healthcare discussion rages, one of the dialectics that feeds the fight is the linguistic meaning of the word ‘rights’. While we all have a fundamental understanding of what this means – something we are entitled to simply because we exist, the differences over the right to healthcare stem from conflicting beliefs about how rights are idealised, and from these idealisations, how they should be enforced.

The right to health is an essential component of human dignity, and governments have a responsibility to protect and advance it for all people, regardless of gender, race, nationality, religion, or financial situation.

The Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) found in Part IV of the Constitution, guarantee social and economic equity for all citizens, especially in matters of health policy. Part IV of the Constitution, therefore, has something to do with health-related government policies, either directly or indirectly. Governments must preserve and advance the Right to Health, and they must put policies and programmes in place to advance and improve the health of all people, especially the most marginalised and disadvantaged groups.

According to a 2019 NITI Aayog assessment, India’s states have unequal public health systems. This imbalance was mostly caused by a lack of technical skills and financial restrictions. While fiscal dependency on the Centre remains a key concern, moving health to the Concurrent List would result in excessive bureaucracy, red tape, and institutional limits. Even if state policy decisions remained subject to the political orientation of the federal government, this centralisation would deprive states of their constitutional rights. Furthermore, a unified approach will not provide the specialist attention that India’s states require.

On a critical issue like health, coordination between the Centre and states must occur without impeding cooperation efforts. Lessons learnt from the response to COVID-19 also demonstrate the need for the continued inclusion of health in the State List even though effective cooperation between states and the Centre is essential. Therefore, it is crucial to decentralise authority and resources to the states so that they can strengthen their public health systems. For instance, despite initial difficulties, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar were able to contain the Japanese encephalitis epidemic in 2019.

Information needs to be available, accessible, and propagated amongst people to successfully allow the inspection of decisions made by the government and the institutions it maintains. Along with responsibility and dependability, transparency is a fundamental, ethical value. The practice of openness will aid in maintaining the control of drug and medical service inflation, ensuring the proper operation of public institutions, and retaining the public’s trust in matters about the right to health and healthcare.

India has several issues concerning the right to health. Inadequate healthcare infrastructure especially in rural regions is one of the main problems. Only 1.4 beds, 1 doctor, and 1.7 nurses are available for every 1,000 residents in India as opposed to the standards put forwards by the WHO.

According to research, majority of the healthcare infrastructure is concentrated in large cities, leaving the remainder of the population without access to even the most basic healthcare services. More than 33% of people in India still have infectious diseases according to a Frontiers in Public Health paper. With only INR 7.28 and INR 29.38 for inpatient and outpatient care respectively, the per capita out-of-pocket expense for infectious disorders is likewise significant.

Following are some ramifications of implementing health as a fundamental:

The right to equality protected by Article 15 upholds the prohibition of discrimination based on religion, race, caste, gender, place of birth, and other factors. a. It overturns discriminatory systems that are present in the healthcare industry. Healthcare is now a privilege only available to a few groups of people due to decades of poor investment in public health.

- Inequality in all facets of life, including education, opportunity, wealth, and social mobility, will persist without the constitutional right to health, which is essential for dismantling discriminatory structures.

- Strengthen people’s capacity to demand better healthcare and hold the government and healthcare professionals accountable by enacting legislation that makes healthcare a right, the government would be improving the entire health ecosystem.

- c. Constitutional right to healthcare will pave the way for special legislation, capable institutions, increased budgets, medical training, research, wellness, prevention, and outreach of services; thereby strengthening the entire health ecosystem.

Challenges with implementation:

Lack of infrastructure: India’s healthcare ecosystem lacks the necessary support systems to meet the needs of a large population. For instance, India only has 8.5 beds available for every 10,000 residents.

Inadequate human resources: The ratios of doctors to patients (1 every 1456 patients) and nurses to patients (1.7 per 1000 patients) are substantially lower than WHO requirements, which are 1/1000 for doctors and 3/1000 for nurses, respectively.

India has the lowest public health spending as a percentage of GDP among the BRICS countries. Brazil has a rate of 3.96%, followed by Russia at 3.16%, South Africa at 4.46%, and China at 3.02%.

High illness burden: Tuberculosis, diabetes, and malaria are among the most common communicable and noncommunicable diseases in India. To combat chronic diseases, large investments in healthcare infrastructure and resources are required. Hospital infrastructure, particularly secondary and tertiary care, is concentrated in urban areas. This has an impact on the rural population’s access to healthcare facilities.

Pushback from the healthcare industry: As shown in Rajasthan, doctors, and private hospitals reject such attempts, fearing that they will be overworked and their compensation will be inadequate.

A major adjustment in our approach to healthcare is required. Instead of seeing it as spending, we should regard it as a high-yield investment that can significantly reduce future out-of-pocket costs while simultaneously increasing productivity. On a critical issue like health, coordination between the center and states is required without hampering cooperative federalism, which is a key component of the Indian Constitution.

Images:

- https://www.escr-net.org/sites/default/files/styles/original_adap/adaptive-image/public/images/health_care.jpg?itok=g3hCGuMq

- (20+) Facebook

- https://swachhindia.ndtv.com/after-seven-decades-of-independence-why-is-health-still-not-a-fundamental-right-in-india-63139/

References:

- Right to health (who. int)

- Article 21 in The Constitution Of India 1949 (indiankanoon.org)

- https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2020-02/Annual_Report_2019-20.pdf

- Narain, J. P. (2016). Public Health Challenges in India: Seizing the Opportunities. Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 41(2), 85-88. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.177507

- Patel, V., Parikh, R., Nandraj, S., Balasubramaniam, P., Narayan, K., Paul, V. K., Kumar, A. K. S., Chatterjee, M., & Reddy, K. S. (2015). Assuring health coverage for all in India. The Lancet, 386(10011), 2422-2435. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00955-1