Photography has come a long way; from the tedious hours in a dark room to a picture-perfect printout in a few seconds, just as medicine and medical education have. From rote textbooks and didactic teachings to interactive video-based learning, medical education is growing to be one of the most interesting fields to pursue. Often enough, at least one faculty describes how difficult it was for their time, how they had to spend hours at the libraries with fat textbooks versus the ease with which we know our screens. What then has changed is the simplicity with which we can create photographic evidence.

Looking back at the early years of medical photography, it all started in 1839 with the French physician Alfred François Donné who first depicted pictures of platelets and Trichomonas vaginalis. The first patient to be photographed was a woman with goitre by Scottish David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. Englishman Dr Hugh Welch Diamond was one of the first to photograph his psychiatric patients for diagnostic purposes. Dr Samuel P. Hullihen photographed the first dermatological case of a thermal burn. Dr Hermann Wolff Berend in the field of surgery began the practice of pre and post-op photographs. Neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot with Albert Londe worked on incorporating photography in neurology.

How are we using photography in medicine? Firstly, it is the essence of documentation – be it for legal reasons or just for patient information. Everything needs to be put into a file for posterity and proof. Second, photos are forever. There is no altering the past, which gives us an apt idea of what has happened to the wound, lesion, or ulcer 10 days after the intervention. Third for diagnosis, from MRIs to ultrasounds we now move into the world of live imaging and videography. The intraoperative optical coherence tomography is helpful in immediate diagnosis and treatment. Finally, for education – be it patient education or for those budding fresh medical minds.

Patient Education – Cornerstone to Recovery

Image source: Pixabay

I have been a stern believer that once the patient understands the magnitude of their disease and is encouraged to comply with the treatment, the first hurdle to recovery has been jumped. Not only photographs of their diseases but those of people who have recovered is key to showing them that not all hope is lost.

One of my fondest memories during my early years was skimming through the beautiful pages of Gray’s and Netter’s Atlas of Anatomy. Learning is best when seen, heard, and felt and the human body is a visual subject. While the names and synonyms do describe very well, how much can you leave to your imagination? Photographs of the normal, abnormal, and unique are the best way to be educated about the depth of medicine. Sometimes, through the hum-drum of the hospital routine and overwhelming paperwork, many of us miss out on rare diseases. Photographs are a beautiful way to be aware of such diseases. On the other hand, few common findings are difficult to fathom as well, in these cases photographs are a perfect medium of teaching.

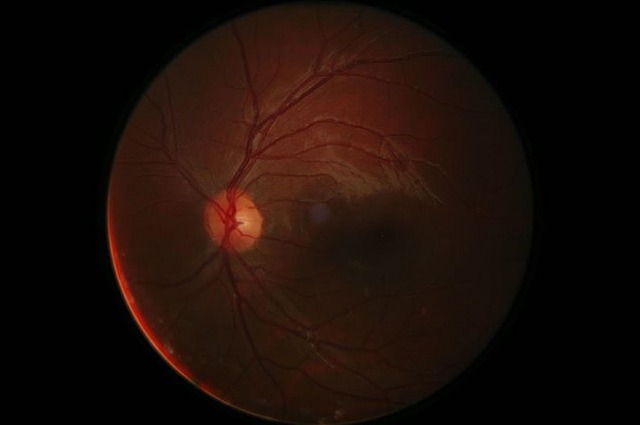

Ophthalmology is very visual for the subject as well as the object in discussion. From diagnostic devices like the handheld fundus photographs, optical coherence tomography and, the ultrasound B scan, we have simple slit lamp mounted cameras, and smartphone attachments for cobalt blue fluorescence photography to follow up on corneal ulcers. Videonystagmography is another brilliant innovation that allows us to record the eye movements of a patient with nystagmus and determine its true nature and form.

Respect their Rights

Photographs also pave a way for research and reporting. Publishing rare cases or new methods of treatment of established cases is a simple way to promote information. While this sounds as simple as clicking the shutter button, one must keep two aspects of medical photography in mind. First and foremost, the patient and their consent. None of this is possible without them, their understanding, and their agreement. Informed consent should be taken for the photograph as well as the clear use for research or publicity purposes. They should not feel pressured into it and should understand that they have the right to refuse. Second, it is of utmost importance to maintain the patients’ dignity and anonymity while taking and publishing the images. Just a line over their eyes and a few blurred areas are not enough to hide one’s identity. Names and identifying numbers should be erased as well. Respect the patients’ privacy and rights.

Medical Photography at the Tip of our Fingers

Not only can we take photos in a second with our smartphones but social media and simple web searches have made it the perfect and quickest way to learn. From googling “proliferative diabetic retinopathy” or “ scleroderma” to using the 9 Gaze app to take post-operative photographs, smartphones are a real boon. Several social media pages are promoting image-based information – be it on Facebook or Instagram. Pages like Retinography ( @retinography, Instagram ), Young ophthalmologists Society of India (@yosisocietyindia, Instagram), The New England Journal of Medicine ( @nejm, Instagram) use these portals to share regular photographs and photo-based quizzes. Videography and video sharing via the internet – by extension of photography – have also helped share information internationally. iFocus by Centre of Sight was primarily designed as a crash course for final-year ophthalmology residents. With covid booming over us, they had to get innovative. It began as it was earlier planned to be – a crash course but now has grown into this wonderful online portal with lectures from distinguished faculty national and international. Individual doctors have pages promoting their cases and surgeries – because sharing is growing together. Wheelessonline.com is one of the orthopaedic go-to pages run by Dr Clifford Wheeless. Internal Medicine specialists vouch by British Journal of Medicine, uptodate.com, 2minutemedicine.com for regular updates. Messaging apps are another brilliant way people have been communicating information. Telegram and WhatsApp groups are a rich source of photos, videos, pdfs of everything you can think of.

Standardization of photographs is one of the building blocks to understanding and appropriate comparison. Proper positioning and centring of the subject, neutral backgrounds, adequate lighting, and correct magnification is the key to good photography. Though it is difficult to replicate the matching variables every time, nevertheless, it should not deter us from trying. Remember to have a scale beside the specimen to project the correct aspect: ratio and size. Understanding lighting and appropriate use of the flash is essential as well. It also helps to be aware of special instruments in different fields such as in dermatology using infra-red or ultraviolet techniques or ophthalmology with fluorescence and autofluorescence. Dentistry, endoscopy, and orthopaedics require specialised equipment for different angulation and handling. Microscopes, bronchoscopes, arthroscopes, and other forms of endoscopes all come with in-built cameras for recording.

While a few hospitals have a designated department of photography, shouldn’t we be properly trained to take these photographs? Isn’t medical photography an integral part of the field? Architecture has photography as a paper in their first year. It does make us wonder why we do not have a separate subject in our curriculum teaching us these norms, instead of us learning it by trial and error.

Medical photography has travelled from standard film photography to specialised filters and portable equipment. While this field continues to grow, we as physicians must always remember to be humane, treat our patients as people first – not as objects of a study. Medical photography is the essence of learning so continue to contribute to the ever-growing rolls of knowledge.

References:

-

A Brief History of Early Medical Photography – Clinical Correlations [Internet]. Clinicalcorrelations.org. 2016 [cited 19 November 2021]. Available from: https://www.clinicalcorrelations.org/2016/09/30/a-brief-history-of-early-medical-photography/

-

Harting M, DeWees J, Vela K, Khirallah R. Medical photography: current technology, evolving issues and legal perspectives. 2015.

-

Puthalath A, Gupta N, Samanta R, Singh A, Kumawat D, Mittal S. Cobalt blue light unit filter – A smartphone attachment for blue light photography. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2021;69(10):2841.

-

Bhattacharya S. Clinical photography and our responsibilities. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2014;47(03):277-280.

-

Nayler J R. Clinical Photography: A Guide for the Clinician. J Postgrad Med [serial online] 2003 [cited 2021 Nov 19];49:256-62. Available from: https://www.jpgmonline.com/text.asp?2003/49/3/256/1145

Comments