We’ve all heard of Pavlov’s dog, Soviet physician Ivan Pavlov’s famous experiment that explained the psychology of conditioned reflexes. Pavlov’s work in digestive physiology revolutionized the study of medicine, and his extensive experiments and findings earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1904. However, his methods were far from ethical by today’s standards.

Pavlov and his associates ran a laboratory in St Petersburg and over a career spanning six decades, Pavlov experimented on thousands of dogs. They were incarcerated, starved, tortured, stressed, vivisected and killed — he famously once said “I will now shred dogs without mercy”.

He performed numerous research trials, mostly relating to the physiology of digestion, and the psychology of conditioning and stress — and innumerable dogs were sacrificed in the process.

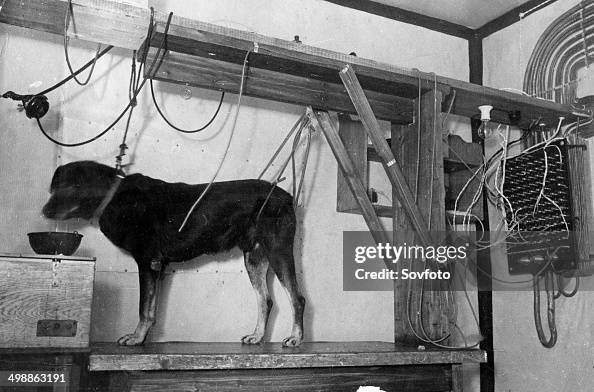

Image 1: A dog set up for one of Ivan Pavlov’s experiments. Source: Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Pavlov’s biographer, Todes, writes that contrary to popular notions, Ivan Pavlov never trained a dog to salivate to the sound of a bell, but rather, to stimuli such as a metronome, a harmonium, a buzzer, and non-auditory stimuli such as electrical shock and light from an electric lamp. The misconception initially began due to a mistranslation of the Russian word for buzzer, zvonok, perpetuated by repeated references in the mass media to the “Pavlovian bell.” With these stimuli, all dogs reacted differently: some reacted predictably, some could not be conditioned, and some had mental breakdowns due to the electric shocks. He also used methods such as starvation and isolation to induce stress responses and neuroses to study behavior and psychology.

He performed various procedures in his surgical ward to produce dog subjects for chronic experiments, including gastric, salivary and pancreatic fistulas, esophageotomy, vagotomy, etc. The measurement of the quantity of saliva was done through the insertion of one or more fistulas into a dog’s cheek or neck to divert saliva from three salivary glands into a measuring container. According to one of his students, Pavlov’s favorite was the sham-feeding experiment, done with an esophagotomized dog with salivary fistula. Food consumed by the dog excited its appetite but swallowed food could never reached the stomach —instead falling out of the stoma of the esophagostomy and back into the feeding bowl. Still hungry, the dog would keep eating, and all the while, the gastric secretions produced flowed out through a fistula and were collected. The lab also successfully created dogs with a “Pavlovian sac” — an isolated stomach pouch that opened to the surface through the abdominal wall, to study the secretory activity of the stomach.

Image 2: One of the many dogs Pavlov used in his experiments, with a surgically implanted saliva catch container in the dog’s muzzle. Preserved at the Pavlov Museum in Ryazan, Russia. 2005, Wikimedia Commons

Pavlov’s dogs also enabled his lab to produce large quantities of pure digestive juices, produced in the basement from esophagotomized dogs by sham feeding. The gastric juices created a sensation and were sold in the medical market, and by 1904, the lab produced and sold more than 3,000 flagons a year. The profits helped to increase the lab budget by 70 percent. In fact, the enterprise was so profitable that an assistant was hired and paid thirty rubles a month to oversee the facility. Todes describes the process as follows: “Five large young dogs, weighing sixty to seventy pounds and selected for their voracious appetites, stood on a long table harnessed to the wooden crossbeam directly above their heads. Each was equipped with an esophagotomy and fistula from which a tube led to the collection vessel. Each ‘factory dog’ faced a short wooden stand tilted to display a large bowl of minced meat.”

Through all the surgical procedures, experimentation and psychological trauma, the dogs retained their cheerful disposition and stayed true to their nature. The dogs used in long-term experiments were kept alive longer than those used in acute experiments. A student of Pavlov reported that “All these dogs, with their double or triple fistulas, have a particularly gay air, and welcome the arrival of their master with expressions of joy. The dogs who are manufacturing gastric juice, pancreatic juice, and saliva, suspended by a double strap under their belly, interrupt their abundant ‘sham meal’ to cast their gaze at Pavlov and to request his habitual caress.”

Pavlov took advantage of and acknowledged the fact that it is natural for dogs to accept suffering for the sake of humans; and that dogs willingly express love and friendship for their master despite their physical suffering. This highlights the exploitative side of Pavlov’s experiments on dogs: the misuse of dogs’ unconditional love towards human. Pavlov even perversely named one of his experimental dogs Druzhok, meaning Little Friend.

Later on, Pavlov performed the same experiments on homeless or orphaned children to prove that the same conditioning results that occur in dogs can be recreated in humans. He believed that humans could learn the conditioned response far more quickly than animals. The experiment was similar to those he conducted in dogs: the child would be anesthetised and fitted with an implant in the salivary gland that measures output. They would be then be strapped to a chair with their hands bound and their salivation was measured just like in the dogs, following the application of a neutral stimulus (squeeze of pressure on the wrist) , and a cookie (the unconditional stimulus) was presented.

To some children, Pavlov attached an instrument that applied pressure to the arm and a tube above the child’s mouth that dispensed cookies when a lever was pressed. When the lever was pressed a cookie was released out of the tube directly into the child’s mouth. Over time the child would start chewing and salivating when the lever was pressed, whether there was a cookie or not.

Pavlov’s merciless experimentation on dogs was undoubtedly barbaric inhumane. However, the research that Pavlov performed on children is a far greater blot on the history of medicine, and can be deemed cruel and unethical by any ethical standard. The use of invasive surgery in children without informed consent of the child and the parent undeniably has far-reaching implications involving the physical and psychological well-being of the children for the remainder of their lives.

All in all, it is not inaccurate to say that the nuances of Pavlov’s work are rarely acknowledged today — the conditioned reflex is discussed in a matter-of-fact manner, without much regard to the way the dogs were treated. This oversight extends to much of the scholarship on Pavlov, where dogs are mentioned merely as experimental tools, not as living beings that deserve care or concern. The aim of this piece was to present a perspective that challenges the norms of animal experimentation and trials. The prevalent notion among the pharmaceutical industry and the scientific community is that animals are passive entities, easily integrated into experimental frameworks to yield data. This discussion hopes to learn from history and bring to light ethical questions about animal welfare in laboratories where animal testing is in practice even today.

References:

- Todes, Daniel Philip. Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Love, Service and Sacrifice: Children and Dog Interactions in the Soviet Discourse in the 1930s by Henrietta Mondry, University of Canterbury.