“I hope the exit is joyful and I hope never to return.”

Frida Kahlo’s famous words could accurately sum up most of the critical care experiences. Medical emergencies have a way of stripping a human of all extraneous businesses to bare necessities of survival- air to breathe and nutrition to sustain life.

A routine patient in the intensive care unit is reduced to nothing more than a severely ailing body sent in for maintenance and hooked on to support. They need to be constantly pricked, probed and tested for signs of recovery, not unlike a malfunctioning laptop that sits rebooting in a service centre.

Despite advances in diagnostics and treatment modalities, the status of the ICU setup has seen very few advances since its inception in the 1960s, as reported by Vincent et al in the 2014 supplement of Critical Care dedicated to discussing Future of Critical Care Medicine (FCCM).

INSIDE AN ICU UNIT:

A medical ICU is the place where heroic deeds are performed on a daily basis. The situation of patients being revived from life threatening situations is understandably frantic, noisy and often chaotic, making the ICU essentially a battlefield on medical premises.

Alameddine et al, reviewed the challenges faced in the intensive care unit work environment an categorised the experiences as physical, emotional, and professional.

Physical aspects:

The physical environment involves dealing with “workplace stressors,” like unfriendly lighting, annoying noise, awkwardly placed equipment, and overcrowding. An ICU nurse is said to perform an average of 200 duties per shift, manoeuvring through a barrage of alarms (lot of which are either false alarms or clinically insignificant), checking flashing screens, and monitoring drips. A lack of space in most tertiary care centres result in constant hospital guideline failures as well as restricted movement during emergencies.

Emotional aspects

In addition to the draining effects of constant vigilance of monitoring, efforts of numbing out the noisy alarms, and the general malaise of the ambience, the ICU staff are burdened with the emotional baggage of untoward outcomes to treatments- deaths. The ICU has the highest mortality rate (15%) among all the departments of a tertiary care centre, and every life lost negatively impacts the morale of the workers. Striking a balance between hope v/s reality, uncertainty v/s decisiveness, compassion v/s professionalism adds to their mental load.

A semiconscious patient lies buried somewhere beneath all the medical paraphernalia. With the staff diligently preening at screens and drip levels, the breathlessness being experienced by the patient is objectively translated to PO2 scores and heartrates. The response to treatments has to be evident in bloodwork and unlike the OPD, the patient is seldom in a position to give a verbal feedback, making the whole process more mechanical than personal. Imagine the irritation of an already sleep deprived patient who managed to drift off for few moments, just to be painfully awakened to have his morning sample collected. A lot of investigative work is carried out by the overworked and impassive staff that barely connects with the exhausted patient. The result is- conditions like ICU psychosis and post-traumatic stress syndrome.

To quote Dr. G. T. Rane, of Rane Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Sindhudurg, India, ‘ICU shouldn’t be all about machines reading men; but men reading men through those machines.’

Professional aspects:

Making sense in the chaos of an ICU takes smooth orchestration among its workforce. In a space where life and death decisions are to be made at the spur of moment, a careful balance between responsible autonomy and cohesive teamwork is required. Additionally, lucid and accessible data records, of a case that keeps fluctuating on a daily basis, need to be logged from time to time. According to Dr Brian Pickering, (Anesthesiologist and Critical care physician at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester) an average ICU patient is said to generate 2,000 data points per day. This translates into an overwhelming amount of data collected within a span of a week that needs to be logged, retrieved and maintained for medico-legal purposes. Keeping the patient’s relatives, who are already on tenterhooks, in the loop is a skill in itself.

ICUs catering to the diverse population of our nation, need to adapt according to the patients they serve and therefore have varied protocols of critical care management.

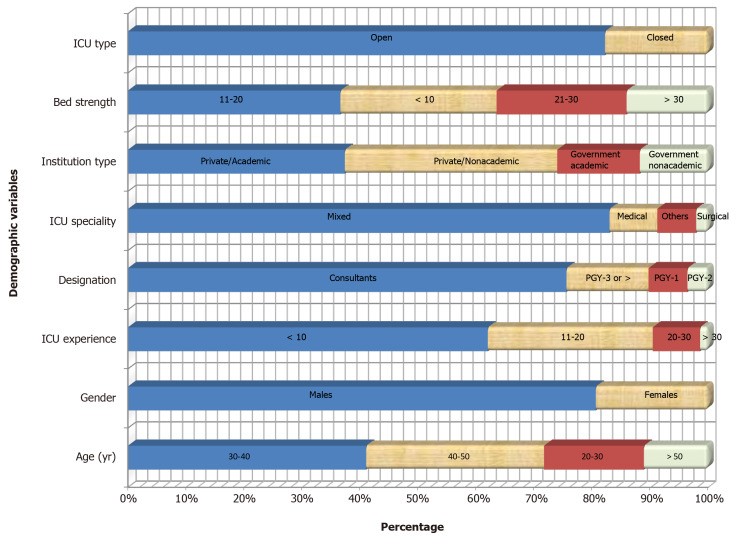

A pan- India survey Indian National ICU Needs” assessment (ININ 2018-I) designed on google forms was deployed from July 23rd-August 25th, 2018 and sent to select distribution lists of ICU providers from all 29 states and 7 union territories (UTs).

Image source: World J Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 5; 9(2): 31–42.

It was found that there was a need for improved manpower including in-house intensivists and decreasing patient-to-nurse- ratio. As sepsis was the most commonly encountered diagnosis the survey findings suggested a need for prioritizing quality and research initiatives to decrease sepsis mortality and efforts to limit ICU stay.

While protocols for glycaemic control, Advanced Cardiac Life support, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, stress ulcer prophylaxis, severe sepsis, ventilator associated pneumonia, and nutrition were found to be in place in most setups, well defined protocols palliative care/end-of-life, delirium, early mobility and targeted temperature management after cardiac arrest were deficient

The authors concluded that, subsequent surveys were required to focus on digital infrastructure for standardized care and efficient resource utilization, and enhancing compliance with existing protocols.

THE 10 BED ICU CONCEPT

The shortage of critical-care services was evident during the second wave of the pandemic.

The 10 Bed ICU project is a cooperative effort, founded by a number of business leaders, involving India’s state governments to set up ICU facilities in hospitals along with an online telehealth platform, connecting remote ICU patients and their local health-care providers with specialist physicians located in faraway medical schools.

The project recently started training local doctors and nurses from remote setups in operating ICU equipment and the telemedicine software.

PARADIGM SHIFTS IN INTENSIVE CARE.

The current status of critical care justifies a modified perspective: emphasis on new approaches identifying effective therapeutics as well as identifying what are effectively palliative situations.

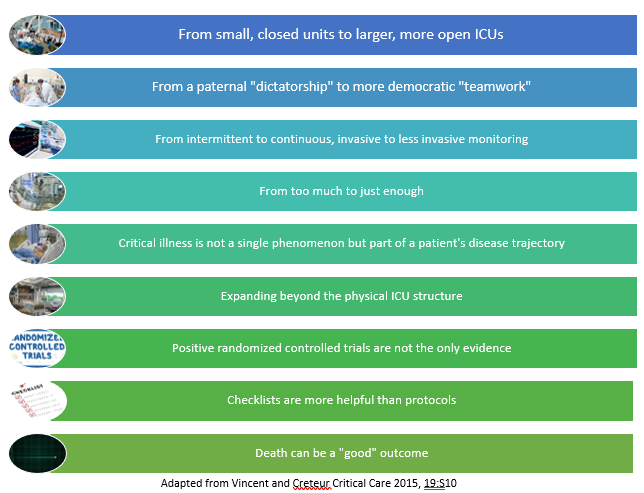

Vincent et al in the 2014 supplement of Critical Care discussing Future of Critical Care Medicine (FCCM) listed certain paradigm shifts that are helping modern ICUs usher into the new era.

Stone et al Journal of Critical Care Volume 35, October 2016, Pages 90-95

Smart ICUs

A great deal of sophistication of technology goes into simplifying intricacies of the ICU. An area that needs to be primarily worked on is diminishing the “alarms race” between ICU devices by interconnecting the various data feed devices and harnessing wireless technologies. Usha Lee McFarling summarised innovations made by doctors in the 2016 article for STAT

Dr. Peter Pronovost, a critical care physician and patient safety researcher at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, (known for introducing the checklist for doctors to be used before inserting a central venous catheter — a simple measure that drastically reduces bloodstream infections), is said to be working to create “smart ICU” by proposing that various data feeding devices ‘talk’ to each other. He introduced use simple sensors to check ICU bed angulations or regulate peripheral compression devices in long term immobilized patients.

It has also been claimed that telemedicine can reduce ICU mortality — mostly by ensuring that nurses and physicians respond quickly when patients begin to deteriorate.

A new secure microblogging platform is being tested in Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, that promises better communication by allowing entire ICU team to view all updates relating to a patient.

Joe Kiani, founder of Masimo (manufacturing non-invasive patient monitoring devices), California, and organiser of Patient Safety Movement Foundation in 2013, believes that free data flow and linked devices were key to improving patient safety.

“Hospitals are finally having a eureka moment,” he reports.

Humanising ICUs

It may take a lot of technological sophistication in building smart ICUs but it takes a lot less to humanise ICUs. Indifferent or disrespectful patient care often accentuates the already harrowing experience of ICUs. Most patients who are lucky to survive the ICU report it as a singularly undignifying experience of their lives. Factors like inaccessibility to personal hygiene, unceremonious arousal from already diminished sleep for repeated investigations/examination, separation from loved ones and forced immobilisation, heavily weigh down on the morale of patients who are recovering from a life threatening condition.

Heavy sedation, though beneficial in pain alleviation is said to be associated with delirium and confusion in patients and also allows a certain level of callousness among the staff members whilst handling such sedated patients, reports Liz Kowalczyk for The Boston Globe.

While many hospitals are trying to cut back on sedation of ICU patients, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston is encouraging their ICU nurses to keep handwritten bedside diaries for unconscious patients explaining their condition and the path to their recovery.

UCSF is testing bedside tablets that can be used by patients or families to upload photos, their experiences, and share what their healing goals are.

The sense of returning to normalcy needs toning down of the austerity associated with most traditional ICUs and a certain level of domestic familiarity that could be incorporated in the ICU architecture. Simple measures like respecting personal space, establishing meaningful communication, encouraging self-reliance wherever possible can go a long way in rehabilitating a patient recovering from a critical illness.

It doesn’t require extraordinary establishment to alleviate pain and fear. When it is all finally over for good, the patients tend to remember the kind touch more than the ill-timed prick for blood work.

References:

1) Vincent and Creteur, Critical Care 2015, 19:S10

https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/cc14728

2) Alameddine et al, Journal of Critical Care (2009) 24, 243–248

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883944108001275

3) https://www.statnews.com/2016/09/07/hospital-icu-modernize/

4) World J Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 5; 9(2): 31–42.

5) Stone et al Journal of Critical Care Volume 35, October 2016, Pages 90-95